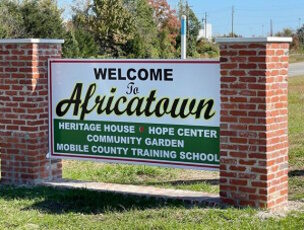

“Clotilda: The Exhibition” will mark the “inaugural installation” for Africatown Heritage House, a new museum opening in Mobile, Alabama, this summer. Specifically, it will open to the public on Saturday, July 8.

Founded after the Civil War, Africatown is a residential area north of downtown Mobile. Many of its residents can trace their lineage to the 110 survivors of the Clotilda, the last known slave ship to arrive in the United States.

“Clotilda: The Exhibition” will share the long-untold story of those survivors. Let’s take a closer look.

A Brief History of Clotilda and Africatown

The following was taken from the press release about the exhibit:

Under the cover of night in the summer of 1860, a ship carrying 110 Africans slipped into Mobile Bay. The Clotilda, the last known U.S. slave ship, made its illegal voyage 52 years after the international slave trade had been outlawed. (Though it was illegal to bring enslaved people into the United States, domestic slavery itself remained legal until 1865.)

Upon arrival in Alabama, the 110 captives were offloaded into the marshes in the delta of the Mobile River. To conceal his crime, the man who had arranged the transfer ordered the boat burned and sunk. After hiding the enslaved Africans in the wilds of the Mobile Delta, he divided and sold them at locations throughout Alabama.

When slavery was abolished in 1865, the 110 dreamed of returning to Africa but did not have the financial means to get there. About a third of them pooled their limited resources to purchase land and transform it into an independent community they called “Africatown.” There they maintained their African identities; continued to speak their native languages; established their own set of governance; and built churches, schools and businesses based on what they knew from their homeland. In the ultimate demonstration of resilience, they created their own world on the northern end of Mobile. This was the only community in the late 19th century established and governed entirely by African-born Americans.

In 2019, the remains of the shipwreck were identified at the bottom of the Mobile River, providing irrefutable proof of a 160-year-old crime. The sunken Clotilda also offers a tangible link to the 110, making their descendants a rarity among the millions of African Americans who long for specific details about when and how their ancestors were forcibly brought into the United States.

The Clotilda Exhibition

Visitors can explore “Clotilda: The Exhibition” at the Africatown Heritage House, a site newly constructed by the Mobile County Commission and the City of Mobile. The exhibit shares the stories of the 110 men, women, and children through a combination of interpretive text panels, documents, and artifacts. It even includes some pieces of the sunken ship.

Africatown Heritage House

The History Museum of Mobile hired the facility’s first-ever manager, Jessica Fairley. She’s eager to share the incredible and inspirational accounts of the ship’s survivors with visitors —whether they come from around the block or around the globe.

“Imagine if people come from all over the world just to hear this story,” Fairley says. “I want Africatown Heritage House to be the Plymouth Rock for Black people. I want people from all over the world to be able to come here, place their hands on the glass (which will encase remnants of the Clotilda) and connect with their ancestors.”

“Africatown Heritage House is a place of hope and pride,” she continued. “You’ll come in and see what these people were able to do after they were taken away from their homes and put in a place unknown to them. I don’t know what my ancestors went through, but knowing what the survivors of the Clotilda went through gives me a piece of my story.”

Africatown Heritage House will open to the public on Saturday, July 8. Then it will be open thereafter on Tuesdays through Saturdays, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

A new trend in American history?

The first thing I thought when I read the press release about the Clotilda exhibition was, “Whoa. More hidden history revealed!”

Because it instantly reminded me of a couple of other times in the last several years when people have pushed to reveal formerly concealed history.

Like HBO’s Watchmen, which shined a light on the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Some Oklahomans were familiar with it, but few others had ever heard of it. And then, shortly after the release of the HBO series, a new study revealed some interesting information about the massacre. Geophysical scanning where it happened identified two possible mass graves that might contain many more previously unknown bodies. (It was one of at least two stories from 2019 that proved the past doesn’t stay buried.)

But perhaps what Clotilda reminded me of most was the story of the Wanderer. On a visit to Jekyll Island, we discovered “The Wanderer” exhibit and memory trail at St. Andrews Beach. Wanderer was also a slave ship. In fact, the second to the last “documented” one engaged in illegally transporting slaves. History-wise, that makes it very closely connected with Clotilda indeed.

For More Info

“Clotilda: The Exhibition” opens to the public the same day as the Africatown Heritage House: Saturday, July 8. After that, it will be open on Tuesdays through Saturdays, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Due to limited capacity, tickets will be sold in time-block increments. You can purchase them in advance at www.clotilda.com.

Check-In

Were you familiar with the Clotilda and its connection to American history? Or is this new to you too?

Courtney Mroch is a globe-trotting restless spirit who’s both possessed by wanderlust and the spirit of adventure, and obsessed with true crime, horror, the paranormal, and weird days. Perhaps it has something to do with her genes? She is related to occult royalty, after all. Marie Laveau, the famous Voodoo practitioner of New Orleans, is one of her ancestors. (Yes, really! As explained here.) That could also explain her infatuation with skeletons.

Speaking of mystical, to learn how Courtney channeled her battle with cancer to conjure up this site, check out HJ’s Origin Story.

I did not know about the Clotilda. What a terrible thing!

But the Clotilda exhibition sounds like an important exhibition. I think I would cry the whole time!

I agree with both of your comments, Priscilla. And I didn’t even think about how emotional it might be. I was angry and crying reading the plaques along the Wanderer Trail on Jekyll Island. The Clotilda exhibit might evoke the same feelings. Which means I better make sure I have tissue available. (You reminded me I think I resorted to using the hem of my shirt at the one on Jekyll.)