“Peopled with garrulous outraged baffled ghosts”—A Grand Tour of Southern Ghosts

The weather was raw and freezing on that fateful January day in a remote valley called Shelton Laurel in the mountains of Western North Carolina. The Civil War had been raging for two long years and the tensions among the hardscrabble farmers who eked out their existence in the valleys, coves, and backwoods of this beautiful, but harsh, landscape, had been heightened. Especially since Governor Zebulon Vance—himself a descendent of these mountain people—had ordered conscription for all able-bodied men into the Confederate army. Secession had been resisted by these strong people who worked their own farms here despite the eloquent pleadings of the refined plantation owners who owned, body and soul, the slaves who worked their farms in the flatter areas of the state.

Confederate troops poured into the Shelton Laurel Valley following a raid on Madison County’s seat, the small town of Marshall. Mountain men, desperate for salt, descended upon the salt stores there and carted away much of it along with some other loot. They had also looted a few homes including the home of Colonel Lawrence Allen where two of his young children lay sick with scarlet fever. News of the raid reached Col. Allen in Bristol, Tennessee and was quickly followed by the tragic news that his two children had not survived the fever. Colonel Allen and Lieutenant Colonel James Keith—childhood friends—marched into the remote valley in search of the men responsible for the raid.

Coming upon a handful of women, the soldiers brutalized them as they refused to reveal the whereabouts of their menfolk. Two elderly women were whipped while two younger women were hung by the necks until they were nearly dead. Another young woman was tied to a tree while her infant child was placed on the snow-covered ground just out of reach. Still, the whereabouts of the men remained a mystery.

The soldiers soon found some fifteen men—ranging in age from adolescents to old men—rounded them up and began marching their rag-tag prisoners towards justice in East Tennessee. After marching but a few miles, the men were stopped and Lt. Col. Keith ordered five of the men to kneel. One of the older men, 60-year-old Joe Wood, begged, “For God’s sake, men, you are not going to shoot us? If you are going to murder us, at least give us time to pray!” Sneering, Lt. Col. Keith ordered his men to fire upon the five pitiful souls. After the first volley rang out and the five dropped quickly, five more men knelt for the last time. Trembling and with halting words in a voice belying his youth, 13-year-old David Shelton pleaded for mercy. The soldiers fired anyway only wounding the boy. His body was riddled with eight more bullets. Within minutes thirteen men lay dead (two of the original fifteen had escaped the previous night).

While the volleys of the executioners’ shot rang out in 1863, the sound of the shots still resound to this day and locals still speak of the tragedy. In whispered tones they also speak of the horror that is still palpable at the site. Tales of ghosts here are not uncommon.

Perhaps no region of the United States can boast more ghosts than the Southeast. The Southern landscape is thronged with legends, lore, ghost stories, and actual paranormal activity that plays out among the live oaks and laurels, pines and palms. From the Mason-Dixon Line south in a crescent line to the Mississippi River, the South possesses a brutal and bloody history, a deep storytelling culture, and diverse and devout spiritual traditions which contribute to its haunted nature. In countless places like the Shelton Laurel Valley, tales of this violence are told and retold and become ghost stories.

Of any region of this country, the South arguably has the most violent past. Even before the Spanish Conquistadors hacked their way through the forests and native peoples of the South, barbarity and bloodshed built the Native American civilizations that originally existed here. Europeans brought disease, misery, slaves, and warfare that brutalized the exquisite Southern landscape. The Civil War brought mechanical murder to the South, baptizing the earth with blood. The sadness that descended on the land after the South’s loss in the war was channeled into bigotry that continues to rend the Southern psyche with hatred and violence. Despite this savage history Southerners developed a refined and diverse culture whose achievements have become marvels recognized worldwide.

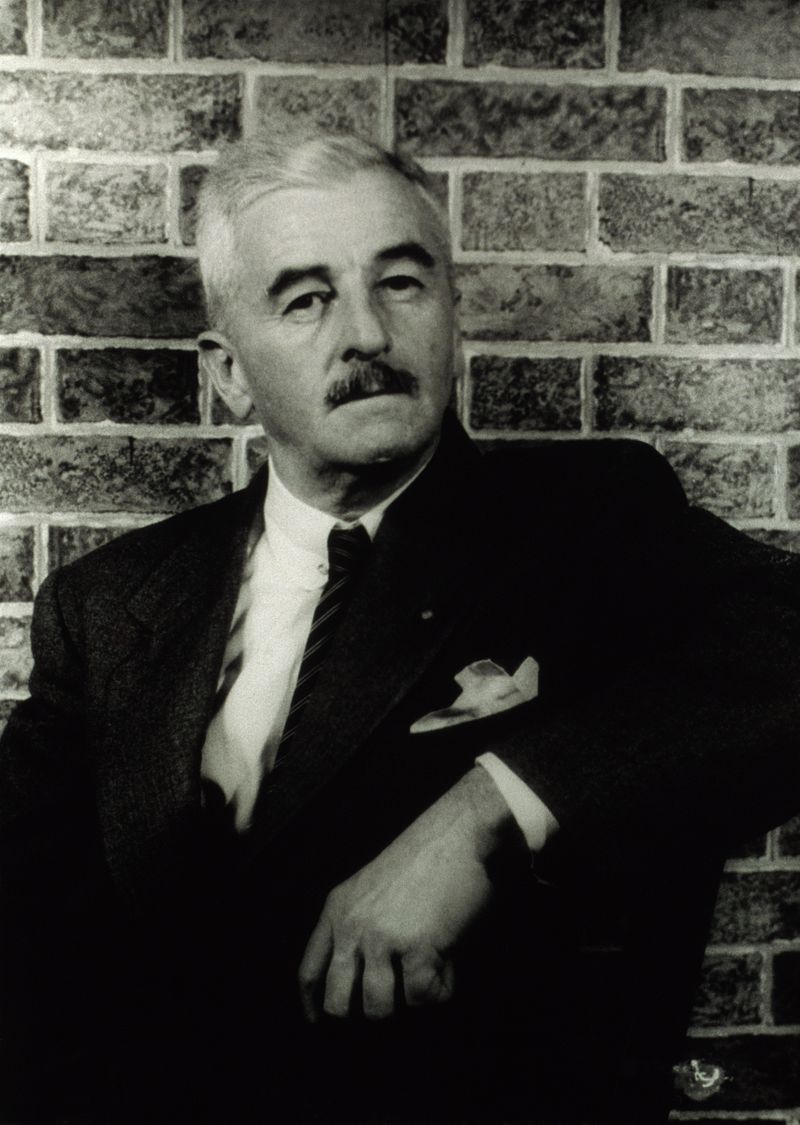

The writer William Faulkner, one of Mississippi’s greatest sons, was weaned on a diet of these stories and intimately understood the inherent violence of Southern culture. His works are woven with the storytelling traditions of the South, often with the same stories retold by several different people, each with their own details and inconsistencies. In his 1936 novel, Absolom, Absolom!, the story of Thomas Sutpen is told through the words of Quentin Compson as he relates this history to his roommate at Harvard University. “Then hearing would reconcile and he would seem to listen to two separate Quentin’s now – the Quentin Compson preparing for Harvard in the South, the deep South dead since 1865 and peopled with garrulous outraged baffled ghosts, listening, having to listen, to one of the ghosts which had refused to lie still even longer than most had, telling him about old ghost times; and the Quentin Compson who was still too young to deserve to be a ghost but nevertheless having to be one for all that, since he was born and bred in the deep South…”

In 1930, Faulkner himself became a part of the South’s ghost story tradition when he purchased a decaying antebellum estate near downtown Oxford, Mississippi, known as the Bailey Place. Surrounded by dense forest, the main house had been unoccupied for seven years and the garden had gone to ruin. Carefully, Faulkner restored the home himself and initially wanted the garden to remain in its ruined state, despite his wife’s wishes to restore it to its original antebellum splendor. From the house and grounds—which he named Rowan Oak after the Scottish practice of placing boughs from the rowan tree over doorways to ward off evil spirits—Faulkner was inspired by the antebellum spirit that remained here in the present.

This coexistence of time periods was heightened by the tragic tale of Judith Shegog, the daughter of Robert Shegog, who built this house in the 1840s. The story generally involves Judith and soldiers during the Civil War and end with Judith’s wan spirit wandering the garden. There are arguments that this tale was simply another literary invention of Faulkner—something he used to entertain his daughter and her cousins—or if the story tells of actual events. Faulkner never wrote the story down so it has remained in the ether of the oral storytelling tradition where it is subject to the changes and evolution that happens with every retelling, though all the stories end with Judith’s tragic death.

Despite the whispered tales of Judith in circulation, there are no accompanying stories of encounters with the antebellum spirit. However, Rowan Oak still has its own actual ghost stories. Staff members have smelled pipe smoke in the house where smoking is no longer allowed. Psychics who have visited the home have noted the presence of a gentleman decked out in a frock coat and top hat who may be the shade of Robert Shegog. Some have even mentioned that he doesn’t understand the parade of guests through his home and he argues that he doesn’t have enough staff to accommodate them with the appropriate Southern hospitality.

Far from the Deep South, the cradle of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, stands the elegant Brice House in distant Annapolis, Maryland where archaeologists combing through common household detritus under the floors discovered an odd cache of objects. Eight bent nails, a glass spindle, a piece of glass etched with a checkerboard design, and a small white disk pierced in the center: a secretive bit of resistance placed there by African slaves and their employed progeny towards their white masters. Secreted under the floorboards of the former kitchen, these small Hoodoo caches were placed to form a cosmogram and thus induce the power of the spiritual world.

What makes this cache even more interesting is its presence in a house that is known for its spiritual activity. Nearly every period of Brice House’s history is contained in the myriad of stories told about its hallowed halls. While a definitive correlation between the home’s haunted history and the presence of the hoodoo cache may be impossible to discern, it does leave interesting questions and serves as a mark of the profound implications of the South’s religiosity.

This deep Southern storytelling tradition is imbued with strong religious sensibilities. Perhaps no region of the country has had such widespread and diverse religious fervor. The land is still touched by the spiritual beliefs of the Native Americans and their spirits and curses still stalk the landscape. With the arrival of the Europeans there is the introduction of pious Catholicism and later puritanical forms of Protestantism into this religious hothouse. Slaves brought their African and Caribbean religions that mingled with their masters’ Christian devotion creating Voodoo, Hoodoo, and Santeria, among other things. Enter Judaism, Eastern religions, pagan beliefs, and even collegiate football into this fertile garden of good and evil to crowd the landscape with competing ideologies, devotion, spirits, and deities.

From lonely mountain gravesites in North Carolina to majestic white-pillared homes in Mississippi to grand colonial homes in Maryland, the dead of Dixie still tread. Florida tourist traps, Virginia battlefields, Alabama factories and Kentucky distilleries are still thronged by echoes of their violent pasts. From small, rural churches and cemeteries in Georgia, the grand halls of government in Washington, D.C., the mines of West Virginia, the swamps and bayous of South Carolina and Louisiana, and the scholarly halls of the University of Tennessee, legends, curses, and the dead themselves clamor to be heard from the lips of storytellers.

Please join me on a ramble to visit among the region’s most imminent spirits, important haunted places, and some of the most paranormally active places among the South’s superb, storied and scarred landscape.

Actor, writer, researcher and obsessive bibliophile. Lewis Powell IV is a native Georgian with eclectic interests including cemeteries, folklore and modern Southern hauntings. He’s the author of Southern Spirit Guide’s Haunted Alabama, which was inspired by the writing he does on his site, Southern Spirit Guide: A Guide to the Ghosts and Hauntings of the American South.