A couple of years ago we took a jaunt up to Pigeon Forge and Gatlinburg. One of the places we visited was Ripley’s Aquarium of the Smokies, which included exhibits about some famous shipwrecks. That’s where I learned about the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Did Gordon Lightfoot’s song, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” play near the exhibit, or simply mention it? I don’t recall now, but I want to say you could hear the song. Maybe it was a matter of pushing a button to make it play? I don’t know.

All I know is that when I heard the haunting, somber melody, I instantly recognized it. And I was surprised because I had no idea an actual event had inspired it.

Let’s look at the Edmund Fitzgerald and its demise, but I’ll go in a bit of a reverse order and share the song first.

The Song

The November 24, 1975 issue of Newsweek included a story called “The Cruelest Month.” Legend has it Gordon Lightfoot was inspired to compose “The Wreck of Edmund Fitzgerald” after reading it.

Thanks to YouTube, here’s a video with the song. (In case you want to see if you know it, refresh your memory about how it goes, or already know but just are in the mood to listen.)

The SS Edmund Fitzgerald

The Fitz, as many affectionately referred to her, was launched on June 8, 1958.

According to the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum, she was “conceived as a business enterprise of the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin.”

Speaking of the insurance company, the ship was named after its President and Chairman of the Board.

She stretched 729 feet and weighed in at 13,632 gross tons. That made her the largest ship to sail the Great Lakes at that time. She held that distinction for 13 years, until 1971.

The Fitz transported ore from mines to the steel mills along the Great Lakes in Michigan, Ohio, etc.

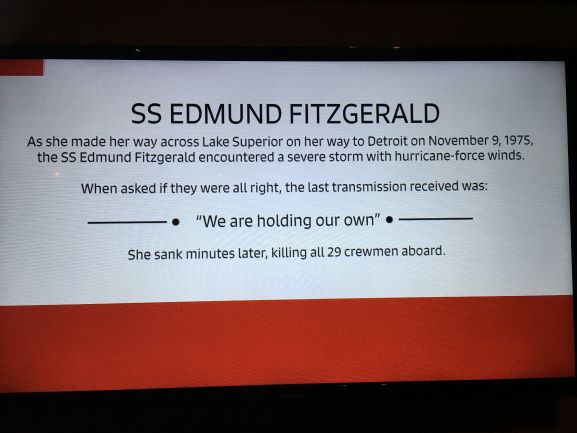

Unbeknownst to anyone at the time, she embarked on her final voyage on November 9, 1975. She was headed from Superior, Wisconsin, with a cargo of taconite ore bound for a steel mill on Zug Island, which is near Detroit, Michigan.

She never made it.

The Wreck

The Fitz departed from Superior, Wisconsin, around 2:30 in the afternoon on November 9, 1975. Another ship, the Arthur M. Anderson, soon joined her. The Fitz’s captain, Ernest M. McSorley, kept in radio contact with Captain Bernie Cooper of the Anderson.

Both captains were aware the weather was going to be rough, but both had also sailed that route in similar conditions before. Except during the night, the weather took a turn, and the next day both ships encountered 35-50 knot winds (50-58 miles per hour) and it started to snow, obscuring visibility. The winds kept shifting and the water roiled with waves.

Around 3:30 p.m. on November 10, Captain McSorley radioed Captain Cooper to say he had some damage, was listing, and was “checking down” (slowing down). He asked Captain Cooper if he could stay by him until he got to Whitefish.

Later that afternoon, around 5:30, Captain Cooper reported the crest of a vicious wave assaulted their boat and wrecked one of their lifeboats. Then shortly before 7 p.m., a “monstrous wave” engulfed the Anderson and even drove the bow into the sea.

The Shipwreck Museum’s site shares what Captain Cooper said about it:

“Then the Anderson just raised up and shook herself off of all that water – barrooff – just like a big dog. Another wave just like the first one or bigger hit us again. I watched those two waves head down the lake towards the Fitzgerald, and I think those were the two that sent him under.”

The last time the Anderson had contact with the Fitzgerald was shortly after 7 p.m. Captain McSorley’s final words to Captain Cooper would be: “We are holding our own.”

Theories About Why the Fitz Sank

The great mystery about the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald lies in the question, “Why did she sink?”

No one knows, but there are a few theories, including:

- Bad weather and high waves.

- A rogue wave.

- Cargo hold flooding caused by improper hatch closures.

The Fitz’s demise might not have been caused by just one of those things. It could’ve been a combo of two or all of them.

Tragedy & Remembrance

Because the Arthur Anderson was closest and the weather conditions were so bad, it was first on the scene in what they hoped would be a rescue mission. They only found debris, including two of the Fitz’s lifeboats, but none of the 29 souls who’d been aboard.

Even though the Coast Guard tried to find the ship right after the wreck, it wasn’t until May 1976 when, with the help of the U.S. Navy, the Fitzgerald’s remains were found.

No bodies were ever recovered, and family members were against the wreck being recovered since it served as a final resting place for their loved ones.

However, in 1995, thanks to advancements in diving procedures and technology, the ship’s bell was recovered. It was restored and is now part of a memorial display to the Edmund Fitzgerald in the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point.

On November 10 every year, the museum rings the bell 29 times, once for each life lost.

In 2020, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Shipwreck Museum’s 45th Edmund Fitzgerald Memorial Event is a virtual one.

The Ship’s Legacy

During her 17 years on the Great Lakes, the Edmund Fitzgerald set “haul records” and entertained boat watchers. Especially because one of her captains, Captain Peter Pulcer a.k.a. the “DJ Captain,” would pipe “music day or night over the ship’s intercom while passing through the St. Clair and Detroit rivers (between lakes Huron and Erie).” He would also entertain “spectators at the Soo Locks (between Lakes Superior and Huron) with a running commentary about the ship.” (Source: Wikipedia)

To have something like that suddenly go missing was quite a shock to many. And a sadness too, because was there anything that could’ve been done to prevent the tragedy?

Perhaps. And as these things often do, good is born of bad.

The sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald changed shipping safety procedures and protocols. New regulations and practices were instituted, like mandatory survival suits, depth finders, positioning systems, and more frequent inspection of vessels.

Plus, it inspired Gordon Lightfoot to write his hit folksong “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” which reached No. 1 in Canada and No. 2 on the U.S.’s Billboard Hot 100 chart. It was also nominated for two Grammy Awards and was one of his biggest hits. The only one bigger was “Sundown.”

Not all tragedies are so lucky to have such a beautiful, if haunting, tribute.

For More Info

Visit the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at https://www.shipwreckmuseum.com/.

Check-In

Did you know Gordon Lightfoot’s song was based on an actual shipwreck?

Courtney Mroch is a globe-trotting restless spirit who’s both possessed by wanderlust and the spirit of adventure, and obsessed with true crime, horror, the paranormal, and weird days. Perhaps it has something to do with her genes? She is related to occult royalty, after all. Marie Laveau, the famous Voodoo practitioner of New Orleans, is one of her ancestors. (Yes, really! As explained here.) That could also explain her infatuation with skeletons.

Speaking of mystical, to learn how Courtney channeled her battle with cancer to conjure up this site, check out HJ’s Origin Story.