One of the most fascinating books I ever read was Michael Capuzzo’s Close to Shore: The Terrifying Shark Attacks of 1916. I didn’t pick the most ideal time to read it, though. It was while we were on vacation in St. Lucia in the early 2000s. I was engrossed in the pages while I was safe on the sand in a beach chair. But the second I put on my snorkel gear and submerged myself in the sea to have a swim around…well, paranoia on steroids set in.

I didn’t know much about the movie Jaws up until that point. Other than it was an iconic horror movie that had scared the crap out of me as a kid. But as I read Close to Shore, there was no denying noting the similarities.

Sort of. I mean, Jaws was set in the 1970s. Close to Shore detailed shark attacks that happened in 1916. But could those incidents have been what inspired the movie? They were eerily similar.

That’s how little I knew about the movie. I had no idea it was based on a 1974 bestselling novel of the same name by Peter Benchley. But whereas Benchley’s book was fiction and Close to Shore was non-fiction that was published almost three decades after the release of both the book and movie, all were based on those real-life shark attacks of 1916.

Let’s dive in for a closer look.

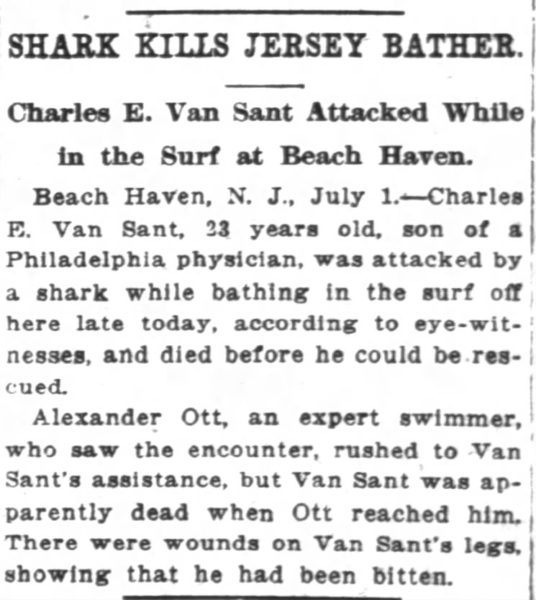

It All Began at Beach Haven

The first victim of the 1916 shark attacks was 23-year-old Charles E. Van Sant. A shark bit his legs while he was swimming at Beach Haven, New Jersey, late in the afternoon. That was July 1.

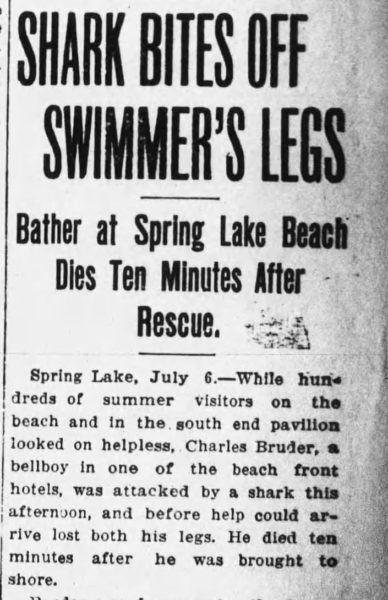

Five days later, on July 6, Charles Bruder, 27, would meet a similarly gruesome fate while swimming up the coast at Spring Lake, New Jersey. In fact, Bruder’s fate may have been even worse, because it was reported in addition to suffering an abdominal bite, his legs were bitten off.

Precautions

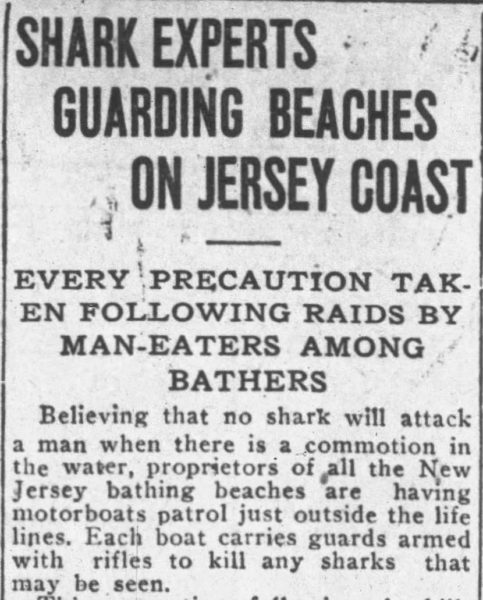

People didn’t know a lot about sharks at that time. Some believed they were harmless and would leave people alone. That they were more afraid of us than we had reason to fear them.

Obviously, two fatal attacks in the same week changed all of that. People quickly realized we were treading in unknown waters —literally and figuratively. But how do you prevent further shark attacks? That was the question resort owners and authorities had to grapple with and solve. Man-eating monsters were bad for business.

One option was to use steel nets that would create a safe perimeter for bathers. Another was to have armed guards in patrol boats. Even better was to combine the two.

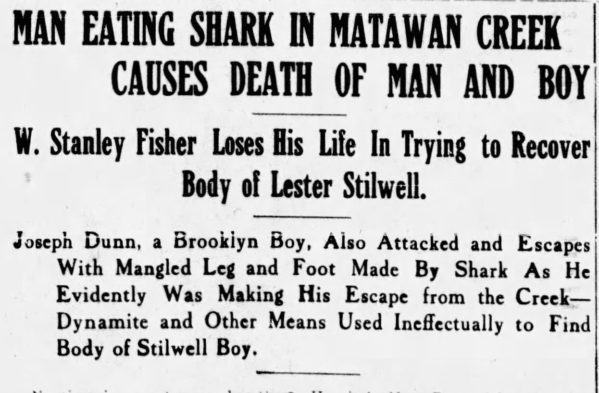

However, then came the attacks in Matawan Creek at a community 11 miles inland from the ocean. That upped the ante.

Terror Inland

Lester Stilwell, 11, was enjoying cooling off in the creek with his friends on July 12, 1916. The boys noticed something in the water, but by the time the dorsal fin rose and they realized it was a shark, it was too late. The shark clamped down on Stilwell before he could scramble out of the water.

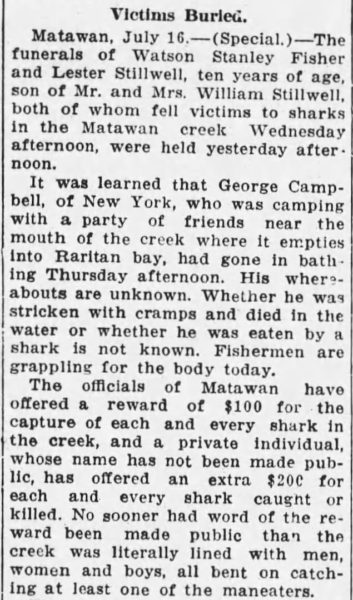

His friends ran for help. One of the men who came to his aid was Watson Stanley Fisher. Stanley, as he was known, sadly lost his life trying to save Stilwell when he bled to death after the shark also bit his leg.

Another boy, Joseph Dunn, 14, was bitten about 30 minutes after the attacks on Stilwell and Fisher. However, his brother was able to pull him from the shark’s mouth. Dunn sustained injuries to his leg but survived.

Shark Wanted: Reward

Rewards were offered to anyone who killed a shark after that. Needless to say, hundreds of sharks were killed in the days that followed the Matawan Creek attacks. Wikipedia summed up the carnage best: “The East Coast shark hunt has been described as ‘the largest scale animal hunt in history.'”

No one knew if it was one rogue shark or several who all of a sudden developed a taste for human flesh.

And why? Some thought perhaps sharks had grown accustomed to being fed from the steamships that once traversed the oceans more frequently before the start of the war. (What would become known as the Great War or World War I.)

But no one knew. They just knew their innocence was shattered. The inviting waters that beckoned them harbored hidden dangers and hungry monsters that perceived humans as food.

The Prophetic Taxidermist, an Old Oar, and the Shark

On Jul. 14, 1916, taxidermist Michael Schleisser set out for a fishing expedition with his friend John Murphy. As they were heading to his boat, Schleisser found an old oar handle without a paddle. As related by Michael Capuzzo in Close to Home, Murphy asked Schleisser, “What do you need that for?”

Schleisser replied, “Oh, it’ll come in handy for something.”

Turns out those were prophetic words.

Later that day, their net snagged something huge. As Capuzzo described it, their small eight-foot wooden motorboat suddenly “slammed to a halt.” Then the boat started being pulled backward.

Turns out they’d caught a shark. One that was threatening to swamp their boat.

Given the recent shark attacks, they knew they were in trouble. They weren’t on a shark-hunting mission. There’s no way they would’ve attempted such a thing in such a small vessel. They also didn’t have any weapons on board, which they needed because just like the famous scene from Jaws, “the shark was rising out of the net and onto the stern, snapping its great jaws.”

Schleisser realized it was trying to propel itself over the stern to get to them with a gaping mouth full of razor-sharp teeth ready to latch onto their flesh. And it would succeed if he didn’t do something and find some way to combat the shark.

Guess what Schleisser ended up using to subdue it? Yep. That oar he’d felt inclined to pick up earlier that day.

They hauled their unexpected prize aboard and headed for the dock. Once there, they realized a few things. One, the shark lacked claspers, which meant it was a female. Two, it was a great white. Three, it was an adolescent.

Which shocked the men after seeing how violently it had acted. Until then everyone assumed the females of every species were demure and non-aggressive. Wrong.

But an even bigger surprise awaited them when they sliced open the shark’s stomach to examine the contents. Which pretty much happened with every shark caught that summer thanks to the shark attacks.

The Contents Inside the Beast’s Belly

Turns out there were flesh and bones inside the seven-and-a-half foot, 150-pound shark’s belly. Human flesh and bones. All told the contents weighed 15 pounds.

At that time there was no DNA testing so it was impossible to determine if any of it belonged to Charles E. Van Sant, Charles Bruder, Lester Stilwell, Stanley Fisher, or Joseph Dunn —or some combo thereof.

But curiously enough, there were no more shark attacks that summer of 1916.

Now, it could’ve been because Schleisser and Murphy had caught the man-eating shark. Or it could’ve been there was more than one shark responsible and all of them were among the hundreds of sharks caught.

We’ll never know.

But there’s also one other curious mystery to this story that remains unsolved…

The Unsolved Disappearance of George Campbell

New Yorker George Campbell was camping with friends when he disappeared while “bathing” (swimming) in Matawan Creek on Thursday, Jul. 13, 1916.

It was in the same area and only a day after the fatal shark attacks that claimed the lives of Lester Stilwell and Stanley Fisher.

Campbell’s body was never found. Whether he drowned and his body floated out to sea or he met with some other tragedy, no one knows. He very well could have been a sixth shark victim, which means it even could’ve been his flesh and bones that were found in that shark’s belly that Schleisser and Murphy caught.

Books Referenced in This Post

Close to Shore: The Terrifying Shark Attacks of 1916

Jaws: A Novel

The above are Amazon links. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. (For which the Skeleton Crew says, “Thank you! That helps cover our website maintenance and hosting fees!”) For more info, visit our affiliates page.

Check-In

Did you know the real-life shark attacks of 1916 inspired the book that became the iconic horror movie?

Courtney Mroch is a globe-trotting restless spirit who’s both possessed by wanderlust and the spirit of adventure, and obsessed with true crime, horror, the paranormal, and weird days. Perhaps it has something to do with her genes? She is related to occult royalty, after all. Marie Laveau, the famous Voodoo practitioner of New Orleans, is one of her ancestors. (Yes, really! As explained here.) That could also explain her infatuation with skeletons.

Speaking of mystical, to learn how Courtney channeled her battle with cancer to conjure up this site, check out HJ’s Origin Story.

I did know the shark attacks in 1916 inspired Benchley, but I didn’t know how many attacks there were and how deadly they were. Such a tragedy. Think I’ll stick to indoor swimming pools!

I was wondering with how well-read you are if you knew that it was based on the 1916 attacks. Yep! It’s such an interesting case. I’m fascinated by it. But then again, that time period…I don’t know why but it draws me in. I swear I lived from the late 1800s to either late 1910s or early 1920s in a past life. Not a long life, but it must’ve been an exciting one or a good one because I’m quite fond of that era. That’s why this shark story captivates me the most of any I’ve ever heard.